One Good Question

Blog Archives

One Good Question with Mike DeGraff: Are Schools Destroying the Maker Movement?

This post is part of a series of interviews with international educators, policy makers, and leaders titled “One Good Question.” These interviews provide answers to my One Good Question and uncover new questions about education’s impact on the future.

“In what ways do our investments in education reveal our beliefs about the next generation’s role in the world?”’

There was a call for 100,000 STEM teachers in the US, and since then there have been tons of initiatives, and related funding, to respond to the need (some say too much). UTEACH is a very constructivist-oriented teacher education program for STEM teachers, that began at UT Austin and has spread across the country. Then we saw the launch of Maker Faire™ to showcase STEAM design in informal learning space. When I went to my first faire 3-4 years ago, I was amazed that there wasn’t tighter articulation between schools, teacher education programs, and what’s going on in this sector.

In schools, "making" is mostly robotics, especially at the secondary level. School libraries may have makerspaces that are more diverse, but there’s very little happening in teacher preparation for how we prepare teachers for these spaces that are proliferating. No two people have the same vision for what you mean when you say makerspace. Whenever you talk about this, it’s so easy to get excited about the 3D printer, laser cutter and other specific tools. At UTeach, we’re more interested in how it transforms what kids are able to do and how teachers are empowered to teach differently. Not to dismiss the tools, but ultimately, what’s so exciting about all of this stuff is how it connects to this lineage of progressive education dating back to Dewey and meaningful, authentic, relevant work. That’s what’s so powerful to me about this whole maker movement. It really champions student voice in a way that I don’t see in any other movement/innovation/fad. How can we replicate that for every kid? One of the biggest hurdles in education and industry is to get kids curious. Makerspaces can get them to a point where they can start wondering.

The maker world and project-based formal education don’t seem to respect each other enough. The maker world which is super auto-didactic, self-sufficient, diy, vibrant and very curious. The maker world sentiment is that schools are going to destroy the maker movement by embracing it and standardizing it. It’s not an unfounded fear. Look at the computer labs in the 90s. The way that education works is in compartmentalizing. My biggest fear is that it becomes a space where you go and do « making » for an hour completely separated from (or only superficially connected to) science, math, language arts, literature, art, etc.

The formal education world is coming from a perspective that we’ve been doing « making » well before Maker Faire started in 2006, but have called it other things like project-based instruction. Colleges of Education see the value in makerspaces, but in public education we have to focus on serving every kid. While the Maker Education Initiative motto is « every kid a maker » colleges of education and educators in general are asking what do we do with kids who aren’t motivated by blinking a light or don’t identify with the notion of making? How does PD play out in these different areas and what does it look like as these spaces develop?

“Do you think that schools/universities would be adopting Makers Spaces if it wasn’t tied to funding?”

These spaces have always existed in universities, but they used to be highly articulated with coursework. Making in a university is usually housed in the college of engineering, which makes sense for digital fabrication and electronics. You were typically a junior before you got to that level of coursework and only accessed the equipment for specific, course related projects. If you talk to industry, a big complaint is that universities are producing engineering graduates who can calculate, but can’t use a screwdriver and a hammer or connect that academic experience to the real world.

A makerspace is more similar to a library type model so it’s open and you can go in and make when/what you want. UT opened a Longhorn Maker Studio and when I went there in November it was full of kids making Christmas presents (like ornaments, a picture frame, and other highly personal artifacts). There’s a lot of class projects, but it’s more about figuring out what they can do with it. That’s what’s exciting.

Something that I see as very similar to the makerspace idea in the College of Science is open inquiry where students choose what they want to learn more about, design an experiment, and analyze results. In UTeach, one of the nine courses is totally dedicated to this process. Instructors have noticed that the hardest part of the process is to get students to become curious. Get students to develop their own questions that can be addressed by experiments. In education, we have identified content, but the gap is how we inspire students to be curious and engaged and motivated and passionate. It’s so well connected in general to how we get students to think and be self-motivated and have internal drive.

“One could argue that Makers spaces are going the way of MOOCs — only reinforcing the privilege and access of middle-class paradigms and still largely unused in lower-income/marginalized communities. If we really belief that Makers spaces improve creativity, critical thinking and STEM, what will it take for the movement to reach a more diverse audience?”

Why I see maker movement as being fundamentally different, is that I see it as hitting on different things, namely on student motivation and constructivist education, with what we know about how students learn best, project-based instruction, and the evolution of progressive education. At the UTeach conference last May, we had several sessions about making in the classroom. It’s important for us is to embed this into regular coursework. Right now, a lot of the robotics and electives are afterschool activities, but in order for this to be truly democratized, we have to make it part of our classes—science and math that every kid takes. NGSS and CCSS math standards demonstrate value for persistent problem solvers, design cycle and implementing inquiry. Makerspaces can support these standards for all students.

As part of the maker strand at our UTeach conference Leah Buechley gave the plenary talk contrasting mainstream maker approaches with tools and techniques designed to support diversity and equality.” This is exactly why we, in education, need to systematically develop opportunities around « making » for a more diverse population, which early indications show is working. We’re already seeing that the demographics of youth-serving maker spaces are much more diverse than that of Maker Faire.

Mike’s One Good Question: How can we use this space to address community needs ? What we’re doing is making things, but why are we making them?

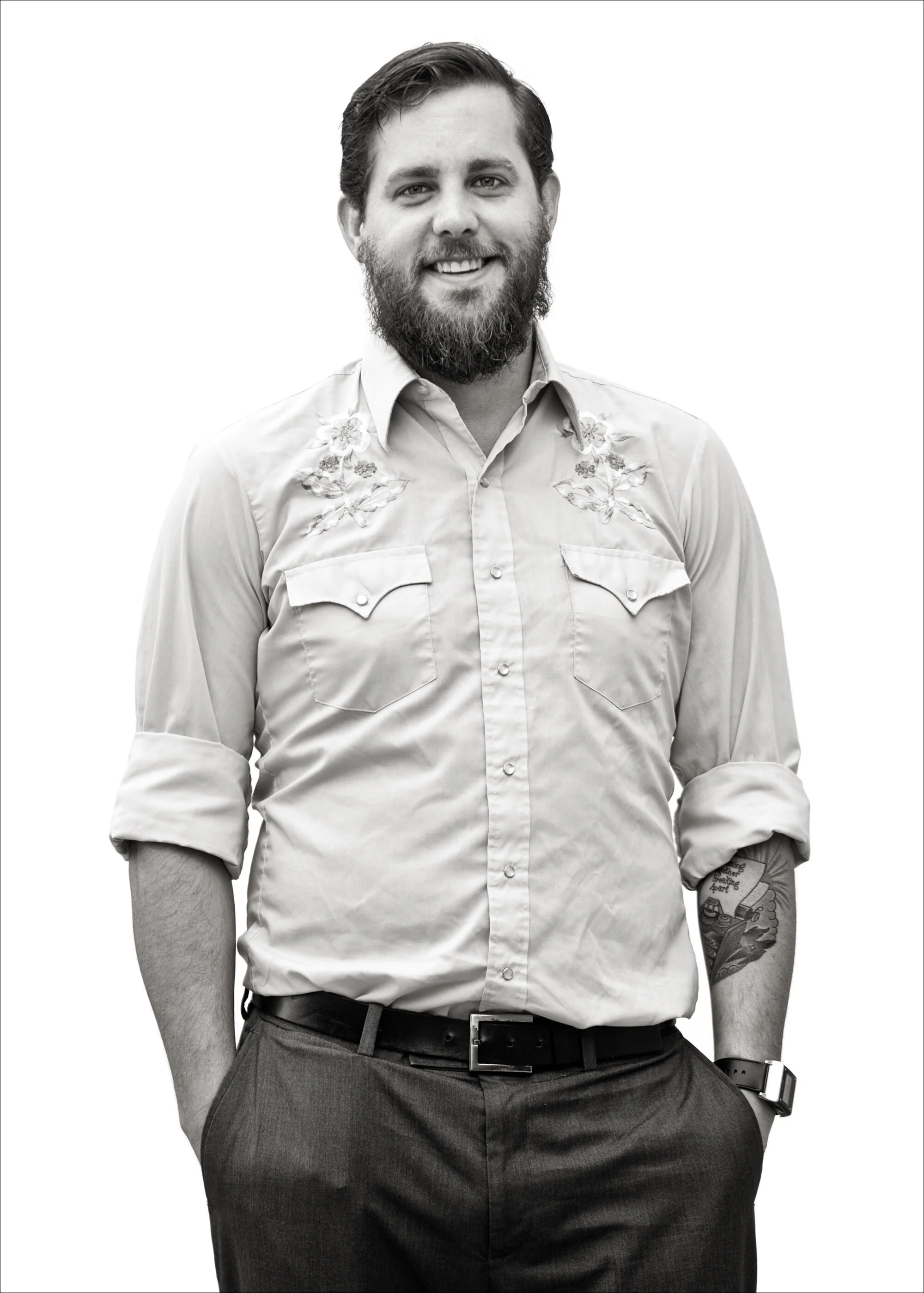

Michael DeGraff is the Instructional Program Coordinator at the UTeach Institute. His work includes coordinating the Instruction Program Review process for all UTeach Partner Sites as well as supporting instructors to implement the nine UTeach courses.Michael has been a part of UTeach since 2001, first as an undergraduate student at UT Austin (BA Mathematics with Secondary Teaching Option, 2005), then as a graduate student (MA Mathematics Education, 2007), and finally as a Master Teacher with UKanTeach at the University of Kansas. He was also instrumental in launching Austin Maker Education.

Didn't Get the Answers You Wanted in 2015? Maybe You're Asking the Wrong Questions…

But when you start thinking you know everything, you stop being curious.

I started 2015 asking, what, I thought, was a bold, reflective question for the year. It was our first morning in Havana, and we were introduced to the ceiba tree and her place in Cuban history : meetings, prayer, dreams, wishes, gratitude. I took a solemn walk around the ceiba tree three times, asking for clarity for the year ahead. My professional and love lives were exploding in ways that felt beyond me. I hoped that the ceiba would help me quiet my heart and brain, and eventually show me the right paths for both sets of complex needs.My ask for clarity was steeped in doing life better. Work better. Love better. Improve outcomes. Change behaviors. I thought those would be the right answers and that the ceiba would help mefigure out how to execute them. As 2015 draws to a close, I have certainly gotten the clarity that I asked for, but the answers were not what I wanted. Here I sit, nursing a broken heart, on the other side of a painful work transition, and questioning everything again. Before the ball drops this week, I want to commit to asking the right questions for 2016, not necessarily getting the right answers. Something manageable between « What is the meaning of life ? » and « What are my interim goal metrics ? »This weekend, Ravi Gupta penned an article about the need for students to engage in deep questioning. « When a student does not have courage, time, and space, their questions are often basic or vague — and sometimes don’t evenend with a question mark. Can you help me? . . . I don’t understand . . . This is hard. » Sound familiar ? He’s described my ask for clarity perfectly. I hadn’t asked a deep question, but made a vague plea for help. What if I had applied his advice for how schools can teach students to question, to guide my adult inquiry?

There is a gap between what we ask for, what we can intuit, and what we actually need to learn. In Ian Leslie’s forthcoming Curious, he focuses on the paradox necessary to remain curious--- understanding enough about something to find it interesting, but not having the answer be so complex that questioning is overwhelming and unattainable. The right question fits uncomfortably in that space, inspiring us to ask and giving us hope that the answer(s) are totally within reach.This fall, I started asking myself questions about my beliefs in education, trying to test how I wanted to serve my professional purpose. Those questions were a step up from vague clarity, but they were still statements in disguise. They were really easy to answer and justify with rich examples from my work. I had brilliant responses to those questions, because they didn’t force me to reconsider my position, to adopt a different perspective, or to learn. Then it occurred to me that I couldn’t answer my own question with the same knowledge that asked it.

So I went back to my inquiry and, this time, decided to ask my peers and colleagues around the world to weigh in. Not just the peers who would mirror my perspectives, but those who had completely different ways of seeing the question. In One Good Question, I ask international thought leaders and doers in education to reflect deeply on their country’s investments, policy, and practices. Throughout the fall conversations, every interviewee noted that facing the One Good Question challenged their own thinking (victory for questioning !). For many, they were unsure if their country leadership was asking themselves this type of essential question to inform education design/reform. How many of our country policies, state priorities, and school practices are based on the right answers to the wrong questions ?There's an inherent tension about the urgency of public education transformation. I get it.We don't feel like we have the luxury of time to reflect, iterate, and deepen adult learning because we’re trying to make swift, scalable transformation for all kids. But if, as leaders- and I mean all of the ways that we lead in this movement -- we're asking the wrong questions, those « wrong » questions will still give us answers. If we’re not asking complex enough questions, we might even be convinced that we have the right answers.The questions that we ask matter, so we should give ourselves the time and space to ask the right ones.

Tensions in Formal vs. Informal Education Solutions.

During the break-out sessions at the GNF Women’s Forum, I participated in “Leaders as entrepreneurs, entrepreneurs as leaders” and “Innovations & challenges in education” and was pleasantly surprised to hear how the conversations blended so seamlessly. Entrepreneurs from around the globe raised questions about the role of formal education in preparing youth to lead. “How can we teach our students differently? How can they learn to harness the opportunities in their environment? How can they learn to be entrepreneurs? In Africa, we can’t create jobs for all of our people. I wish that there was a way for the schools to give them the skills to create jobs for themselves. How can we give skills to students to make them more self-sufficient?”One of our facilitators, Irina Anghel-Enescu (EF, Romania), is on the jury for Global Teacher Prize and asked us directly if we thought the entrepreneurial ecosystem would be improved if educators taught these skills explicitly. All of the finalists for last year’s prize shared an entrepreneurial spirit—they created new models, founded schools, and expanded education access. While they are all highly impactful teachers in their parts of the world, what set them apart was their entrepreneurial mindset and how they took the initiative to change outcomes for all of their students.

There is a growing debate about the role of formal education vs. informal education to prepare this generation for the future. When our conversation took an overly critical turn of formal education, Pilvi Torsti (EF, Finland) of Helsinki International Schools reminded us that these are not competitions. Me & My City is a Finnish example of how formal and informal education partner in the best interest of learning. We have to invest in both levels for deep national or systemic change. She shared that Finland’s decision to invest in education was made when it was a poor agrarian country. Pilvi encouraged us to invest in our human capital now. All sectors need to make conscious decisions to value formal education and integrate role models from other sectors into the sphere.Our panel during the “Innovation in education” session continued to explore this tension. Bernardine Vester (EF, New Zealand) gave an overview of how the marketization and commodification of education has impacted New Zealand and asked what the growing privatization of education means for equity and inclusion. Amr AlMadani (EF, Saudi Arabia) shared his start-up success for how deep, intentional partnership of informal education (robotics and STEM competitions) and formal education is reinvigorating student interest and parent support in his country. Maria Guajardo (Kellogg Fellow, Japan) brought in cross-cultural perspectives on leadership and women’s empowerment. Common threads across their diverse experiences: formal education alone does not change social practices, expectations, or real-world outcomes.

“What’s missing is not the tools. Everybody is watching, but nothing is changing. Passion and love of the game is missing.” – Amr AlMadani

In Saudi Arabia, education has a high cultural value and high government investment (25% of budget towards formal education), yet those two high-level alignments have not inspired passion-filled teaching and learning. Instead of blaming teachers, parents, or cultural practices, Amr decided to offer a solution to the passion question and inspire learning and positive parent participation.Maria inspired our group conversation with her One Good Question : As we become more globalized, how do we lead across differences? How does leadership look the same or different? For her, the question of intersection—where leadership development intersects with culture and tradition— is essential. Education has to be the vanguard for leadership change.Like in every group of education thought leaders, our participants challenged each other to consider different lenses:

On questions of feminization and devaluation of formal education: It’s the economy, stupid. How can we look at the curve of where education attainment and economics meet (personal earnings and GDP)?

On questions of the role of women in formal leadership spaces: The perception of being a leader is different in various cultural contexts. You can be a leader outside of the home and inside of the home.

On equality/inclusion: Can we explore this more? Urbanization and growth of the middle class are all supporting the privatization of education. Does it have to be a negative view or is it an opportunity for more people to come to education? Making the whole system public doesn’t seem realistic at this moment at all.

On informal education: Are there growing demands within our countries where privates are stepping in to fill the gaps? Particularly where the state has failed minority/marginalized populations? Are we seeing this growth and is it a long-term positive trend?

In NZ we moved from social democratic state to one more focused on markets. I have not given up on public education, which is why I’m working with a nonprofit group to insure that t the best teachers end up in the schools with the highest poverty needs. The rising social inequalities arise out of the growing tendency to commodify education and marketize it. It’s no use trying to hold back the tide. How do you use the process to ensure that those who have the least get the most potential? Their potential is our future. Most of the students in Auckland are no longer white and middle class. They’re brown. WE have to do something about it.

Developing Student Agency Improves Equity and Access.

In the summer of 2006, I moved my family from Brooklyn, New York, to St. Louis, Missouri, and began searching for the right learning community for my children and myself. On the heels of teaching in Middle Years Programme (MYP) and Diploma Programme (DP), I found that most urban schools were expecting minority students from low socio-economic communities to consume knowledge and not inform it. I started my own inquiry into school design. What if we offered the most engaging, academically rigorous education to an intentionally diverse community and made it free for all students? What if all children had access to the same education as children of world leaders? If they all learned to be bilingual and see the world through different eyes? If they saw themselves as change agents in their communities now instead of waiting for others or older versions of themselves to take action?When I founded St. Louis Language Immersion Schools (SLLIS), our vision was to create a total immersion, IB continuum school network of public schools. Our first three elementary schools, The Chinese School, The French School, and The Spanish School are authorized for the Primary Years Programme (PYP), and the secondary campus, The International School has begun their candidacy for MYP. All schools represent an intentional commitment to diversity: Title I, ethnic diversity that mirrors or exceeds that of our region, language and country of origin diversity, and family composition diversity.

We expect our school community to be one where students ask, “Why are we studying this? What does it have to do with my life? I’m seven, what can I do about it?”

And our teachers respond with relevant text-life connections and extend opportunities for age-appropriate action. Our grade two students are given their first action challenge as part of their unit on rights and privileges. Teachers ask what rights the students want to advocate for. Students identify rights, who they would need to lobby (siblings? classmates? teacher? parents? administrators?), and then embark on a campaign for change. When our second and third grade cohorts make sophisticated arguments for changing the uniform policy, adding multi-stream recycling, or using lockers, our adult community encourages them and engages in real-time conversations for change.

Look where SLLIS’s staff come from!

One of our first fifth grade exhibitions opened with a student from The Spanish School asking about fear. She began with a pie chart that revealed the most common fears: clowns, barking dogs, abandoned houses, and scary movies. Number one fear? Abandoned houses. Then she adeptly shifted to a map of GIS data depicting the number of abandoned houses in our city and shared her first conclusion: this means that people are afraid to visit my neighborhood, and residents, may be afraid to come home. She then linked the census track with the highest concentration of blighted property and correlated it to personal crime that revealed higher rates of crime in these neighborhoods as well. She continued with examples of the same phenomenon in other urban areas across the country. What can we do about it? Invest in neighborhoods with services—fill the vacant properties with schools, community centers, art projects, give people something to come home to, all in the name of reducing their fears about urban communities.

Yes! This was exactly the type of reflection and attention that will prepare our urban student population for greater access and attainment of post-secondary studies and career paths.

When we talk about the success of IB World Schools in improving excellence and equity for a diverse population, let’s remember that this goes beyond performance metrics. What are the ways in our schools and classrooms where low-income and/or minority students are expected to lead purposefully? Where they are confidently challenging the text, their peers, their teachers, themselves? Where they are marrying analysis and action? Let’s share the stories of students who are changing their world because of inquiry-based learning. The agency and advocacy that students develop in PYP schools is an essential step in bridging the equity gap.

One Good Question with Karen Beeman: How Biliteracy Supports Social Justice for All.

This post is part of a series of interviews with international educators, policy makers, and leaders titled “One Good Question.” These interviews provide answers to my One Good Question and uncover new questions about education’s impact on the future.

“Voy a una party con mi broder."

When Karen Beeman gave this example of a typical statement from a bilingual student, the room of language immersion educators nodded and smiled in agreement. We had all heard our students mix languages before. But Beeman’s point was not about the typical interlanguage that occurs during language acquisition. Her example was of children whose first language is bilingual. Kids who inherit this natural mix from their bilingual homes and communities and learn later, usually in school, to separate the two languages.In her practice at the Center for Teaching for Biliteracy, Beeman contends that we need to acknowledge that while bilingualism is a starting point for many of our students, it is not the anticipated outcome. She prides herself in making education research accessible for K-12 teachers and this workshop exemplified that belief.

Just a few minutes into her talk, Karen had the audience building linguistic bridges between Portugese and English to understand how the practice would support student constructed learning. To the untrained eye, bridges look like translations and Beeman knew that, once teachers created their own bridges, they would see the value in leading their students through this construction.Karen has dedicated her career to elevating and protecting the status of minority language in a majority language education system, specifically Spanish in the US. When I sat down with her to talk about her One Good Question, I assumed that her focus would be on investing in language minority education. What I learned, however, was far more about her vision for all youth in our country. Karen grew up the child of Americans in Mexico and when she moved to the States for university, she had the unique perspective of appearing American and having strong linguistic and cultural identity in Mexico and Mexican Spanish. Karen quickly became an education advocate for bilingualism and champion for elevating the status of Spanish in urban communities with significant Hispanic populations.Karen’s inquiry starts from that place of language specific, culture-specific instructional practice and quickly progresses to questions of social justice and equity: How are we preparing minority students to see themselves in the culture of power ? For the 71% of ELL youth who speak Spanish[1], access to bilingual academic communities that support literacy in both languages, means that they get to comfortably exist in majority culture.

"When students feel visible and what is going on in school matches who they are, we reach their potential." - Karen Beeman

For bilingual and heritage students, this visibility begins with equal access to and respect for their home languages. Karen is agnostic about the type of academic model schools choose. Traditional bilingual, dual language, and two-way immersion programs are all built around English language expectations. What makes the biggest difference? Looking beyond the monolingual perspective and the English dominant perspective. "We cannot use English as our paradigm for what we do in the other language," Karen insists.With respect to the pedagogy and materials in current Spanish-language programs, Beeman contends that we’re creating our own problem. Most texts in bilingual classrooms (fiction, non-fiction, and academic) are translations into the non-English language. This means that they are translating English grammar and syntax progressions into a language with completely different rules. Bilingual students may miss out on natural, age-appropriate expressions in Spanish and often misunderstand the cultural context of a translated story. Beeman traveled to Mexico for years and brought back authentic children’s literature in Spanish that also didn’t work for her bilingual American students. In written texts the academic grammar and syntax is at a higher register than oral language. Bilingual students whose Spanish-dominant parents may not be literate in Spanish, then have little understanding of the « authentic » text.What Beeman experienced was that neither monolingual contexts work for bilingual students. If we are to capture bilingual students’ full potential, we need a third way. Enter language bridges : a constructivist approach that showcases the background knowledge and expertise of the students, and allows them to access the curriculum and complex ideas in the majority language. Beeman then takes this perspective outside of the classroom : we need to stop imposing monolingual perspectives on education policy, pedagogy and educator training. When we recognize that

We have a language of power (academic register of English) and a culture of power (middle-class, European-influenced discourse) that influence all of our instruction ; and

Our country is becoming increasingly diverse linguistically, ethnically, and socially ;

We quickly understand that the need for all types of language and culture bridges in our instructional practice encompasses the majority of the country. Whether we’re addressing socio-economic status, home language, or student identity, most of our students walk into their classrooms as the « other » in the curriculum. Looking at the trends for increasingly diverse population in the US, we have to ask ourselves what happens when our education system doesn’t embed respect for minority cultures.

Karen’s One Good Question : « How can a student’s experience build on his/her fount of knowledge, both linguistic and cultural ? »[1] Ruiz Soto, Ariel G., Sarah Hooker; and Jeanne Bataloca. 2015 Top Languages Spoken by English Language Learners Nationally and by State. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institue.

Karen Beeman provides national professional development for teachers and administrators in bilaterally and bilingual education. Karen is co-author, along with Cheryl Urow, of Teaching for Biliteracy: Strengthening Bridges Between Languages."

Did I offer peace today?

Too often we expect that peace happens to us, that someone else gives us peace or extends the olive branch. We expect that peace happens around us, institutions and organizations and entities make peace. For this year's International Day of Peace, let's focus on how we are each offering peace to ourselves and others.

One Good Question

"I want to ask one good question."That's all? I can ask one good question now. That's what I thought when I heard my colleague share her intellectual goal for the new school year. I had no idea how difficult it would be to ask my students one good question, a question that wasn't leading, that didn't tip my hand or reveal my beliefs, that didn't force students to defend a single position, nor one that allowed them to respond solely with anecdote and opinion.In the fall of 2003 I was working with new peers in the second year of Baccalaureate School for Global Education in Queens, NY. This was the year that would challenge my teaching forever. Over ten years later, I'm still challenging myself to ask one good question. My work in international education has changed, but the need for good questions remains. In this blog I will be exploring international education and access for all students through multiple lenses, but all with the same question: In what ways do our investments in education reveal our beliefs about the next generation's role in the world?Spoiler alert: I am completely biased. My education career is built on ways that we are increasing access and opportunity for all students to connect with the world outside of their local neighborhood: multilingualism, cross-cultural and intercultural competencies, international perspectives, peace-building, youth action and agency, socio-economic diversity. I look forward to having my assumptions challenged and learning innovative ways that different countries, communities, and schools are answering this question.